How Will My Application be Evaluated?

Understanding how applications are evaluated can help inform your application strategy. This description is based on the processes from the University of Michigan and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, large indicative public research institutions, but the general process is the same at other programs. After describing the process we will summarize the implications and reinforce why it matters for you to understand this.

Master’s degree students are typically evaluated by the department as a whole, often via a committee. Ph.D. students are typically evaluated by individual faculty members (i.e., potential research advisors) with assistance from a committee. However, a smaller number of programs admit Ph.D. students to the department as whole; students match with a research advisor later. The University of Virginia is an example of a hybrid: their PhD admission is based on a faculty champion, but students participate in a “Rotation” program that gives a structured opportunity to match with another advisor. Knowing how, and by whom, your application will be evaluated can help you tailor it.

Graduate Admissions

While the exact details vary between institutions, most programs have a graduate admissions committee responsible for overseeing graduate applications, assessments, and offers. Unlike undergraduate admission, graduate school applications are reviewed by the department (e.g., the Computer Science department). This departmental committee can involve many people:

Faculty. In many cases, this committee is a service assignment for faculty members. Faculty, especially more senior faculty, are expected to allocate a portion of their job effort to department-level activities.

Staff. In some cases, especially at larger programs, non-faculty professional staff assist. Broadly speaking, staff may carry out any of the activities described here except evaluating a PhD applicant’s potential research fit.

Students. In some cases, graduate students may assist. For example, Wes assisted with graduate admissions while he was a student at Berkeley and Madeline assisted with graduate admissions while she was a student at Michigan. In cases we are aware of where students assist, a student is never the sole evaluator of an application.

As one example, for academic year 2024-2025, the University of Michigan CSE PhD Admissions Committee was made up of 10 faculty members (1 chair and 9 representatives of various topical areas), 3 staff members, and 1 graduate student. In that same period, the separate Master’s Committee included 4 faculty members (1 chair, 1 advising, and 2 regular members) and 3 staff members.

While there is some amount of automation, especially regarding numerical scores (e.g., GPA), the committees are generally responsible for providing an initial assessment of each application and then assigning some applications to relevant faculty members for closer consideration. For the master’s degree track, applications may be read by multiple members of the committee. For the PhD track, applications are often brought to the attention of relevant faculty members (any faculty, not just people on the initial admissions committee) who are looking to recruit graduate students in that area.

Typically the committee divides up PhD applications by broad topical area. For example, two of the faculty members of the 2024-2025 Michigan CSE PhD Admissions Committee described above were from the broad area of Software Systems (e.g., Programming Languages, Operating Systems, Databases, Software Engineering, Distributed Systems, etc.). A PhD application that “checks the box” for one of those topics is likely to be initially considered by one of those two committee members.

A strong application that mentions a particular faculty member may be assigned to that faculty member for direct consideration. An application may be assigned to multiple faculty members. An application may also be assigned to a relevant faculty member not directly mentioned. For example, if an application mentions a research topic and a new faculty member was just hired in that topic, that application may be brought to the attention of that faculty member (since that faculty member may not yet have been on the department webpage when the student applied, etc.).

Faculty members may also choose to look through any or all of the applications using various criteria (e.g., area of interest, GPA numbers, etc.) as well as via a search tool that searches within all PDF documents from all applications for text. However, not all faculty members do so. For example, across two decades as a faculty member, Wes recalls doing so two or three times as a new professor at Virginia, and once when joining Michigan. By contrast, during Madeline’s first year as a new assistant professor at UMass Amherst, she went into the database and scanned all of the personal statements and recommendation letters for applications that listed a software engineering professor by name (around 100 applications in total). Of these, she shortlisted 20 for detailed review, interviewed 10, and extended 4 offers. Similar to Wes, she is unlikely to do as thorough a review during future years where she is not hiring students.

Hiring faculty members may also choose to look at any application by name. This can be quite common: if you are a faculty member and your friend faculty member tells you (e.g., at a conference, via email, etc.) that their student XYZ is applying and is highly recommended, you will probably take a look at XYZ’s application directly.

In this light, the committee assigning an application to a faculty member and the faculty member following up on an external suggestion to look at an application flow together into the same result: the faculty member looks at the application and evaluates it.

All faculty evaluating an application (either because they were assigned it or because they found it or searched for it) typically provide both numerical scores and also a freeform assessment. While the criteria phrasing vary slightly between institutions, the Michigan CSE and UMass CICS numerical categories highlight similar aspects:

| Michigan CSE | UMass CICS |

|---|---|

|

|

Michigan also has an automatically-computed metric: Undergraduate GPA & Transcript Taking Into Account Your Undergraduate Institution, Compared to Students Admitted Here In The Last 12 Years. The qualifiers in that metric are a good example of the nuanced considerations in these decisions.

Faculty members can see the completed evaluations of other faculty members and may use this to determine the next steps. If you are a faculty member and you did not find an application compelling and you see that another faculty member also gave it low marks, you gain confidence in not pursuing that student. If you are a faculty member and you found an application to be great and another faculty member found it to be good, you two may decide that you will collectively recruit that student (perhaps as co-advisors, etc.).

Ultimately, a faculty member looking to recruit a new student will consider multiple factors when reviewing an application:

1. How many new students the faculty member is looking to hire (e.g., “Two of my students are graduating, but one of my grants that was funding one student is ending, so I want to hire one new student …”).

2. The relative chance of the student accepting an offer. Fewer than 50% of students who are admitted to a graduate program accept that offer. (Most students, ideally including you, will apply to multiple schools and get into multiple schools. If you have two offers of admission, you cannot accept them both.) A very attractive student will likely also receive offers from many schools. This leads to a subtle tension on the faculty side: the more attractive an application is, the more you want that student, but the less likely you are to end up with that student (because that student will also get other offers and may take one of them instead). As a concrete example, in 2025, Michigan CSE admitted (i.e., extended offers to) 109 students for its PhD track and 58 of those students accepted. In that same year, Michigan offered admission to its master’s track to 218 students and 64 of those students accepted.

3. Whether the student is likely to complete the program. It is generally viewed as a poor outcome for everyone involved if a student accepts an offer into a six-year PhD program and leaves at year five without obtaining a PhD Such a student might have been better served (especially in terms of opportunity cost) by leaving at year 2 with a Master’s degree or not attending a PhD program at all. As discussed elsewhere in this guide, a primary motivation for attending a graduate program is your desired career path (e.g., to obtain a job that requires a graduate degree, which itself requires completing the program). Similarly, a master’s degree applicant who does not appear likely to complete the rigorous coursework required for that degree is unlikely to be selected.

4. For PhD applicants: The expected scholarly output of the student, including research, teaching, advising, service, climate, etc. Does the faculty member want to work with the student for multiple years? Some faculty enjoy working with students who are likely to produce creative and novel research results, some are interested in training the next generation of educators, some need students to help supervise a large research program, and so on.

The final two considerations might be summarized as faculty favoring candidates who are low risk (unlikely to drop out of the program) and high reward (likely to do good things in the program and use the program to meet career goals).

Different faculty and different program contexts may weigh aspects of your application differently. For example, most Master’s degree programs focus predominantly on coursework, and so your GPA, especially your GPA in upper-level technical electives, is viewed as more indicative of your likely success. By contrast, PhD students spend much more of their time doing research and relatively little time taking classes, so GPA may not be as relevant. We describe what various faculty members are likely to consider elsewhere in this guide.

Why Does This Matter?

Why does the way that faculty review applications matter to you? We draw out some implications of this process.

1. Your evaluation may be discarded before it is seen by someone in your research area. If you are focused on a particular topic (e.g., databases) the admissions committee may not contain anyone focused on databases that year. If the committee does not rate your application highly and thus does not assign it to someone, and if the database faculty do not search through all applications manually (such searching is rare) and do not hear about you by word of mouth, then your application won’t be seen by someone in your focus area. Strategy: In this guide, we discuss how to tailor your application, especially your CV and Essays, to mitigate this risk.

2. The Topic Area you select while applying can matter quite a bit. For example, if you have done research in Operating Systems but are also interested in Theory, you might be tempted to check both boxes when applying. However, you run the risk that your application will be assigned to a Theory committee member (e.g., for load balancing) who may not have the context to assess your Operating System accomplishments and may thus not forward your application on. Strategy: In this guide, we discuss how to position yourself, especially if you are uncertain about what you want to do in the future (true for almost everyone, actually, but no one talks about it) or if you have interdisciplinary interests.

3. Some low scores can prevent you from being considered. Because there are so many applications each year, at some selective schools if your GPA (for example) is quite low, your application may not be assigned enough human readers to see your actual merits (e.g., perhaps you have a low GPA but multiple publications). Schools try to avoid this mechanical filtering on scores, but it does happen. Strategy: In this guide, we discuss how to frame your GPA and transcript, as well as other ways to mitigate this risk (e.g., word of mouth, where you apply, etc.).

4. There are many more good applicants than available positions: applicants that are more clearly low-risk and high-reward are favored. This structure sets the stage for the majority of our recommendations for essay writing and CV presentation. Strategy: In this guide, we discuss making your good points easy to grasp for busy readers (structure), being compelling (persuasion), and demonstrating that you are low-risk and high-reward (evidence).

Application Evaluations: Insider View

For historical context, we provide the PhD and Master’s degree numbers for a ten-year span for the University of Michigan CSE division, as well as the internal faculty “dashboard” view of two applicants who have explicitly consented to allowing that information to be published. (That is also true for all other student-specific information in this guide: each student generously consented in all cases.) The data provided are taken directly from UM’s internal system and are what decision-making faculty see. We then describe a less-obvious wrinkle in the faculty decision-making process related to these numbers.

Application Numbers

For the application numbers, the Applied, Admitted and Accepted columns are the most relevant. (Some columns, like “Pending”, may reflect students who never officially responded in time; such cases can be viewed as “Declined”.)

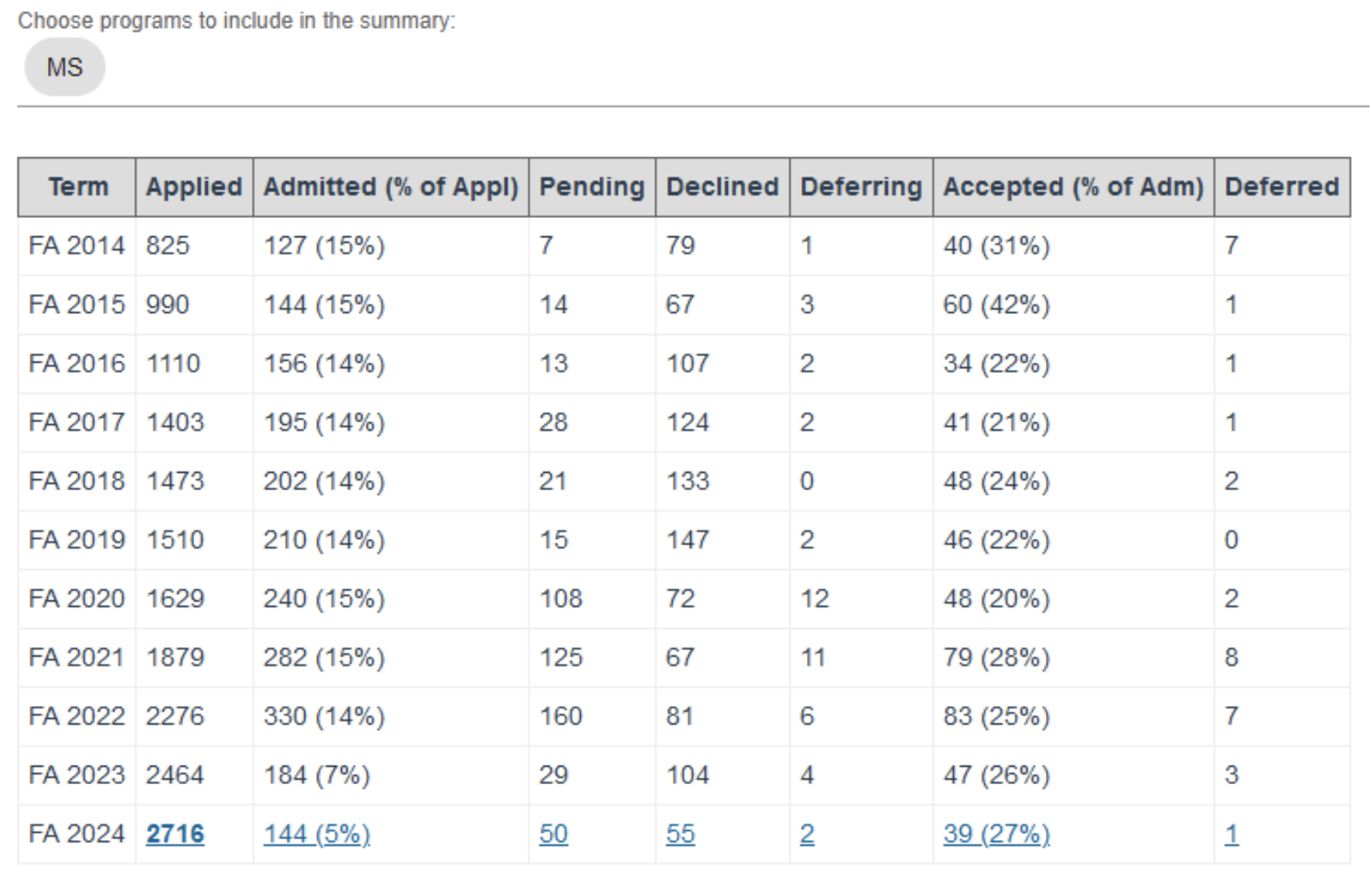

First, Michigan Master’s track statistics:

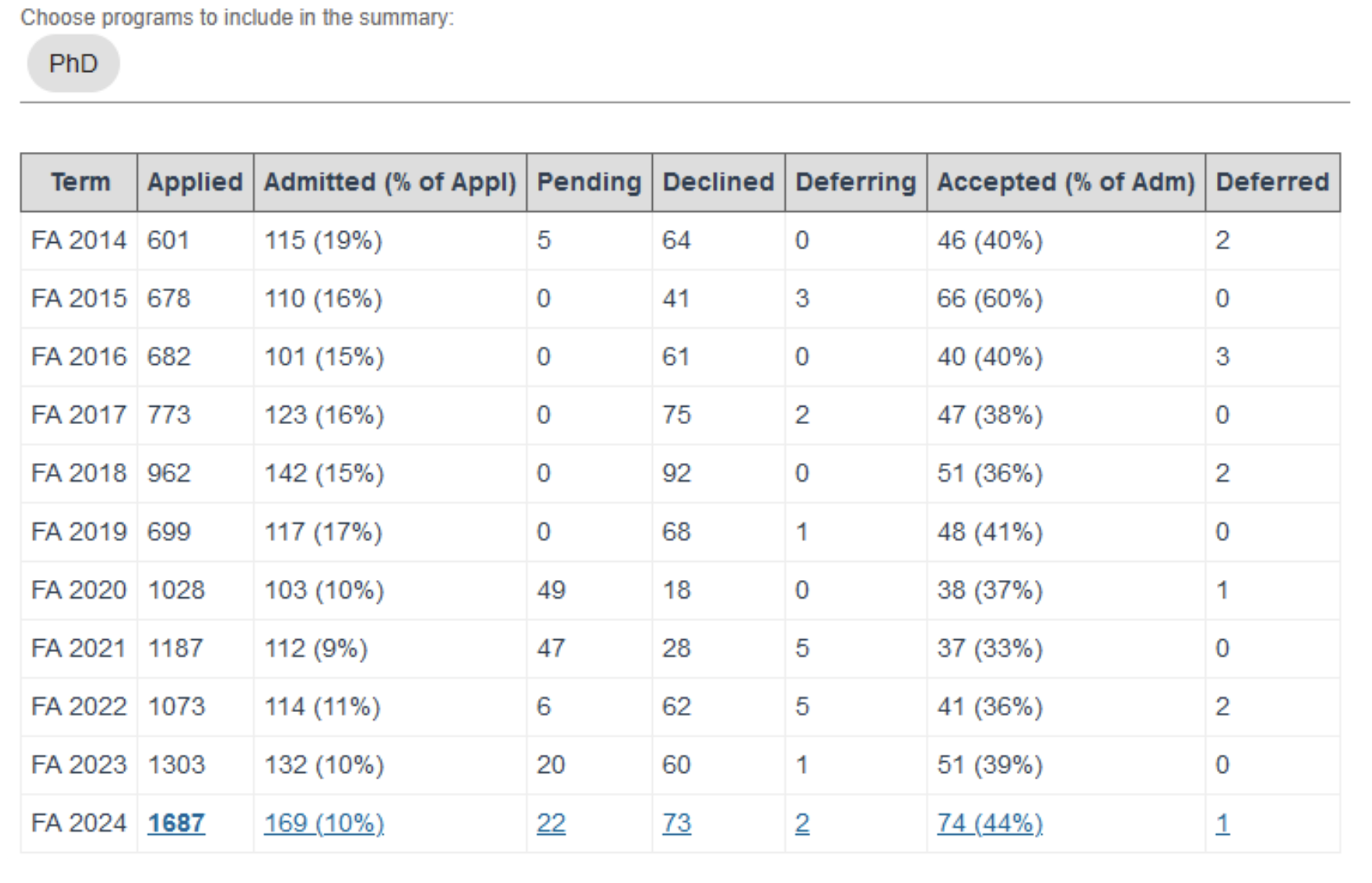

Second, Michigan PhD track statistics:

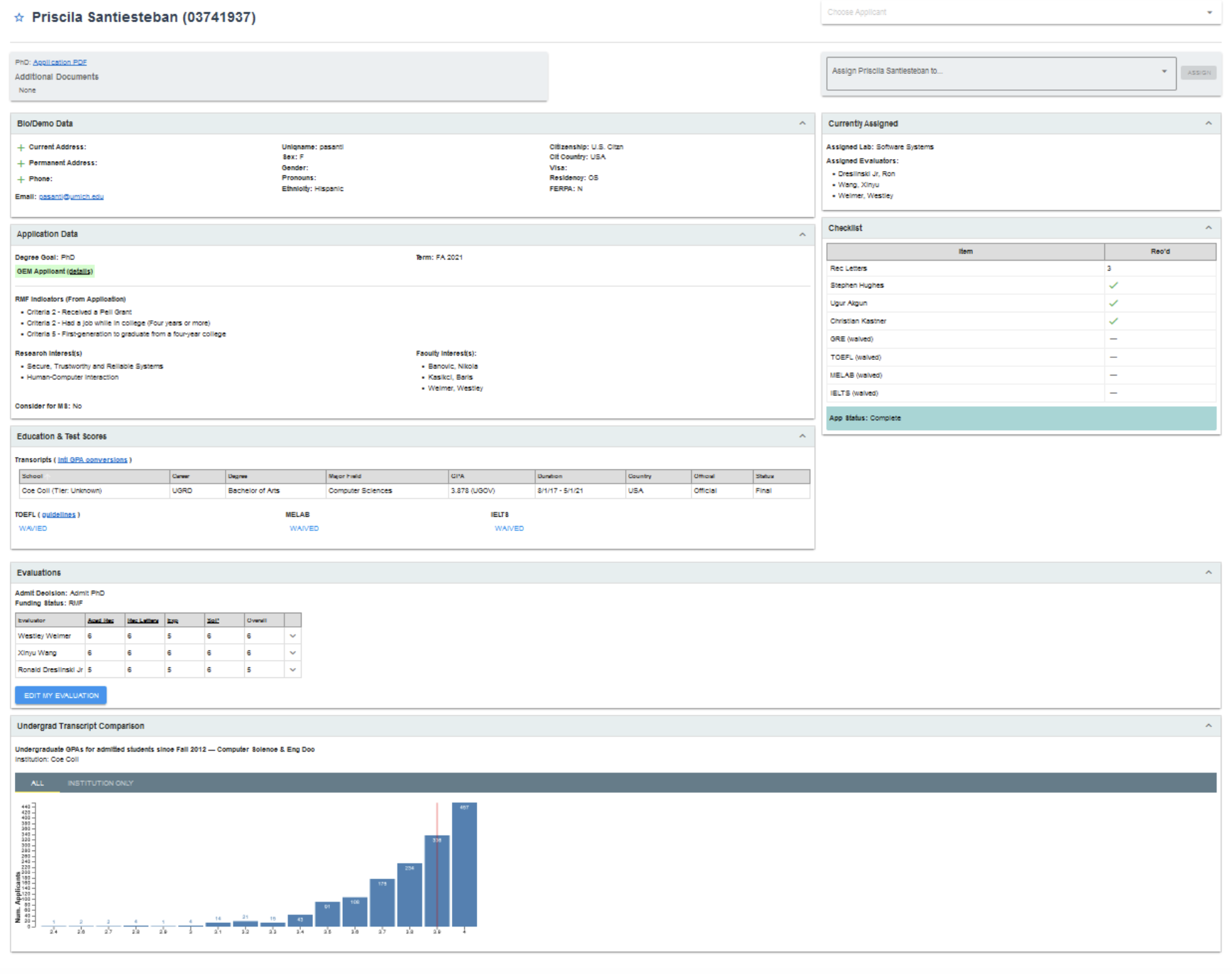

Internal Dashboard View of PhD Applicants

We also present the internal “dashboard” view of two PhD applicants. Faculty can click to see the entire application packet (e.g., application essays, letters of recommendation, etc.). However, this dashboard view is frequently used by faculty making decisions. First, it is usually the initial view faculty have of a particular applicant: if a student doesn’t look appealing in this summary, the faculty member may not take the time to see the full packet (especially given the number of distinct applications; see above). Second, this view is often used for comparisons (e.g., if you are a faculty member and have funding to admit one PhD student but there are three strong applicants, you may flip back and forth between the summaries of the three applicants while considering).

Note the demographic information, research interests, identified faculty members, assigned evaluators, transcript information, graphical presentation of GPA distributions, and scored evaluations:

For this applicant, note how the applicant identified three faculty members (Banovic, Kasikci, Weimer) but was evaluated by others with some overlap (Dreslinski, Wang, Weimer). This can happen for multiple reasons. The most common is that professors read the application materials and decide that the student is or is not a good fit. However, there may be other reasons that are less visible to applicants. For example, at the time Xinyu Wang may have been a newly-hired faculty member in that area looking to grow a research group, and Baris Kasikci may have been leaving Michigan for the University of Washington (and thus not taking on new Michigan students).

In the evaluation area, each elevator gave a numeric score on a 1-6 scale for Academic Record, Recommendation Letters, Experience, Statement of Purpose, and Overall, as well as a freeform prose comment (visible to faculty by clicking on the down arrow to the right of each elevator, but elided in this guide).

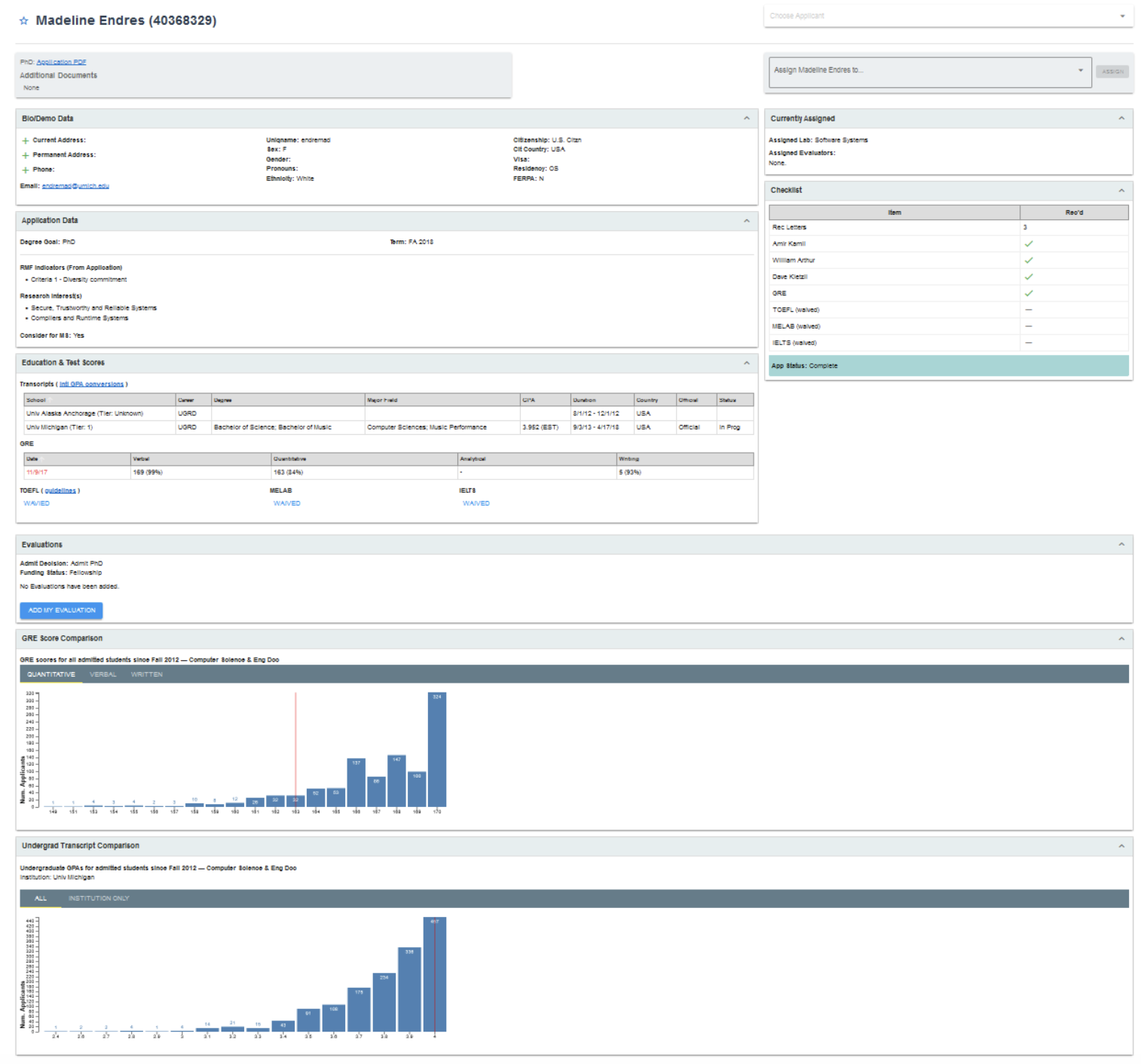

A second applicant dashboard view is also available:

The faculty evaluators and applications are, unfortunately, not available/archived for this older (2018) application. However, note the GRE context view (as discussed elsewhere in this guide, including GRE information is not recommended in modern applications and typically just makes you look worse) and lower-level details, such as “Tier: Unknown” for both one of this applicant’s undergraduate institutions and the previous applicant’s institution. Schools do weight grades by the perceived rigor of the undergraduate program.

The Paradox of “Yield”

One interesting aspect of the initial statistics is that the Acceptance rate (i.e., the percentage of those who receive offers who then go on to accept them, also called the yield on offers) is not 100%. This may initially seem surprising. Wouldn’t a top-ranked school like CMU or Berkeley “get” almost everyone it makes an offer to? When Wes Weimer was on the Berkeley graduate admissions committee, the yield was similar to some of the statistics above (about 25%). The explanation given was that students who apply to Berkeley and receive offers (i.e., students who assess well using the standard metrics) are also likely to apply to Stanford and receive offers there (e.g., because Stanford uses the same standard metrics). And the same is true for MIT and CMU and the like as well. A student who gets into Berkeley and Stanford (etc.) can only accept one of those offers, and from the university’s perspective it ends up a bit like a coin flip: highly-ranked universities typically have under-50% yield.

This can lead to a surprising nuanced effect. Suppose the graduate admissions committee is ranking applicants. “Person X is our #1 choice, Person Y is our #2 choice, etc.” If you are trying to fill ten slots (e.g., you have ten open seats in your master’s program) how many people from your ranked list do you admit? If you extend offers to exactly 10, because of yield, you won’t get all 10. So committees and professors sometimes end up solving mathematical constraints (e.g., “if our yield is 50% and we want 10 people, we should admit 20”). However, the effect is not linear. The farther you go down the list, the more likely it is that the person will accept your offer. For example, if Berkeley and Stanford are both trying to end up with 10 students, the #1 student on Berkeley’s list is probably also high on Stanford’s list. But the #10 student on Berkeley’s list may not have made the top ten for Stanford (slightly different faculty priorities, slightly different assessments of the essays, etc.). Many students take the highest-ranked offer they receive (which is not actually a good idea in general; see elsewhere in this guide on decisions). All of this put together means that the further you go down the ranked list, the more likely you are to get that person (your yield goes up) but the less you want them (they were ranked lower on your list).

This observation helps illuminate how decisions are made behind the scenes. However, it can also inform and motivate some aspects of your applicant. Faculty and committees are often, implicitly or explicitly, ranking applicants. “I only have funding for one PhD student. Should I extend an offer to Wenxin, who published a human study on programming outcomes, or Madeline, who has significant teaching experience but no submitted research work?” Faculty internal deliberations and committee conversations often end up using these one-sentence summaries of applicants (e.g., “Jeremy from Virginia is a returning adult student and submitted a journal article on reducing software energy consumption”). You, the applicant, can either provide that sort of summary in your application materials explicitly or you can have faculty members infer it. When faculty infer it, we sometimes forget important parts of your portfolio. Elsewhere in this guide, we’ll discuss how you can persuasively structure your application materials to provide a summary in a compelling manner.