Life Once You Are In!

Day-to-day life as a graduate student may be very different from what you are used to. That is both a challenge and an opportunity.

While master’s degree students may feel a bit like undergraduates (the graduate courses for a master’s degree can be similar to senior-level technical electives), PhD students often feel quite different, focusing primarily on research rather than courses. In addition, graduate school is usually in a new town (and often in a new country!) and feelings of imposter syndrome are common.

On the positive side, graduate school often involves significantly more day-to-day freedom than the undergraduate experience. Many graduate students report first feeling like a “real adult” in graduate school: greater freedom, greater responsibility, and a decreased reliance on family all contribute to that sentiment.

Semesters

During the two main semesters each year (Fall and Spring), master’s degree students and junior PhD students primarily take graduate courses, while senior PhD students work on research projects.

Graduate students almost always have a desk in a shared lab in the computer science building. Master’s degree students typically have total freedom to work from home or from the office.

PhD students typically work out expectations about in-person attendance for certain activities (e.g., group research meetings) with their advisors.

A full-time graduate student teaching assistant works 20 hours per week as a teaching assistant. Although a standard “full-time job” in the U.S. is 40 hours per week, a full-time graduate student TA position is 20 hours per week. The “other 20 hours” are then spent on graduate coursework and pursuing research. Similarly, a PhD student paid as a full-time research assistant does 20 hours of research work per week on paper (and then typically spends the “other 20 hours” on research as well).

When we talk about a graduate student being fully funded (tuition, health insurance, and stipend), that is associated with 20 hours of paid work per week.

While requirements vary from program to program, master’s degree students typically complete 6–10 courses. For example, the University of Michigan CSE division requires 24 graduate credits and most graduate courses are 3 credits each, for a total of 8 courses. A student could complete these in four semesters (2+2+2+2) or three semesters (2+3+3), and a student who completed one or two courses while completing the undergraduate degree could finish the rest in two semesters (in a five-year bachelor’s + master’s program).

Not all courses are offered every semester, and you often have to take courses from different categories (e.g., at least one Theory course, at least one Hardware course, etc.), so it sometimes takes one more semester than you might think. Overall, a common day-to-day experience for a master’s student might be “three more semesters of taking rigorous courses.”

Junior PhD students also take classes but may take them at a slower rate while working on research simultaneously. In contrast to undergraduate or most master’s degrees where coursework is essential, research progress is the most important task for progressing through a PhD program.

Summers

Summers can be very productive times in graduate school. Most undergraduate students are away, and graduate classes are rarely offered during the summer. Master’s degree students often pursue a paid, external internship during the summer (and students in a five-year bachelor’s + master’s program may not have a summer in graduate school at all). PhD students typically stay during the summer to work on research without distractions but may also go on external internships or travel to conferences to present publications and network.

Vacations

Graduate students have a significant amount of flexibility regarding when they work. Master’s degree students can schedule their time however they like as long as they are passing classes; they typically leave for Winter holidays and other breaks. Similarly, most advisors care more about whether or not PhD-track students are producing high-quality work on time than whether you happen to be in the office on a particular day or not. Graduate school work hours often vary per week, and after pushing for a course project deadline or research paper submission deadline, graduate students often take time off so things “even out” and work-life balance is maintained.

Graduate students paid by the program often have particular obligations. For example, a paid teaching assistant may be required to help grade a final examination at the end of the semester (and may thus not be able to leave on vacation until that is done). Similarly, a paid research assistant may be expected to be present at certain group meetings or help submit a paper by a deadline (and may thus not be able to leave on vacation until that is done).

We strongly recommend that paid graduate students discuss these obligations early with their advisors or supervisors. Some programs provided structured worksheets with good initial questions (e.g., how often do we meet, what are the expectations for vacations, etc., in addition to questions relevant to other aspects, such as how authorship attribution is decided for scientific publications). Multiple examples are available. You can (and should) ask those questions of your advisor even if your program does not provide an explicit structure for it. Advisors and advisees often come from very different backgrounds and it is better to discuss duties directly than to make an assumption.

Stress and Feeling Overwhelmed

Graduate school is often a period of transition, full of firsts both personally and professionally. Throughout the program, students are busy with coursework or research while also dealing with significant uncertainty (e.g., “will I get this internship I applied for, will my research approach produce interesting results?”). Together, this can lead graduate students to experience a significant amount of stress and feel overwhelmed.. At the same time, graduate school can be a great place to learn more about yourself, what you like to do, and who you want to be.

If you experience stress in graduate school, you are not alone. One thing that helped the authors of this guide is actively taking breaks to maintain work-life balance and building a support network of mentors and friends. Many graduate programs have graduate-specific student organizations and clubs that can help build community and relieve stress.

Time Management

Graduate school often involves multiple independent tasks and an expectation that you keep up with all of them on your own. For example, a first-year PhD student might be taking graduate-level courses with readings and final projects while also working as a teaching assistant with grading and discussions while also working on a research project with an advisor. In theory, this is not that different from undergraduate work. In practice, the open-ended nature of the tasks can make it difficult to know when to start one and begin another.

Self Confidence and Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome a feeling of doubt in one’s experiences compared to the perceived accomplishments of others, is almost universal in graduate school students and applicants. While there are many facets of imposter syndrome, part of it may be understood in terms of how we speak with, and compare ourselves with, others. Suppose there are only three activities: research, coursework and being a teaching assistant. Perhaps I am doing well at research, but as a result I did not have time to put into getting high grades in your classes or to put time into being a TA. I may have one friend who did well at coursework and another friend who is a teaching assistant. If I am not careful, I will compare my worst attributes to the combination of all of my friends. In my self doubt, I may not be careful to note that my friend who did well at coursework did not have time for research, and my friend who put time into being a TA did not have time to do well at coursework. Students I have advised who have published papers but low GPAs discount their research accomplishments and worry; students I have advised who have excellent GPAs in difficult courses but no research discount their coursework and worry.

Mental Health

A meta-review found that around one-fourth of PhD students report symptoms of clinically significant depression, and one-fifth report symptoms of clinical anxiety (Nature Scientific Reports, 2021).

Job Market

Graduate school can be described as counter-cyclic with respect to the business economy: the harder it is to “just get a job”, the more tempting it is to make your resume look more attractive by adding a graduate degree. Conversely, if highly-paid jobs are plentiful, the temptation to spend more years “in school” may be reduced. This means that many graduate students are in graduate programs because they want career opportunities, but at the same time, those students are there when career opportunities are more scarce. We have a separate full-length guide on the post-graduate job search (Link).

Housing and New Towns

For many students, especially international students and first-generation students (i.e., students who are the first in their families to go to graduate school), moving to a new college town and building an independent life as a graduate student can be daunting. Many experience a very significant culture shock. Activities of daily living, from grocery shopping to public transportation, may be vastly different from what one is used to. This can be a significant part of the subjective experience of being a graduate student, especially in the first year or two.

Overall Reflections

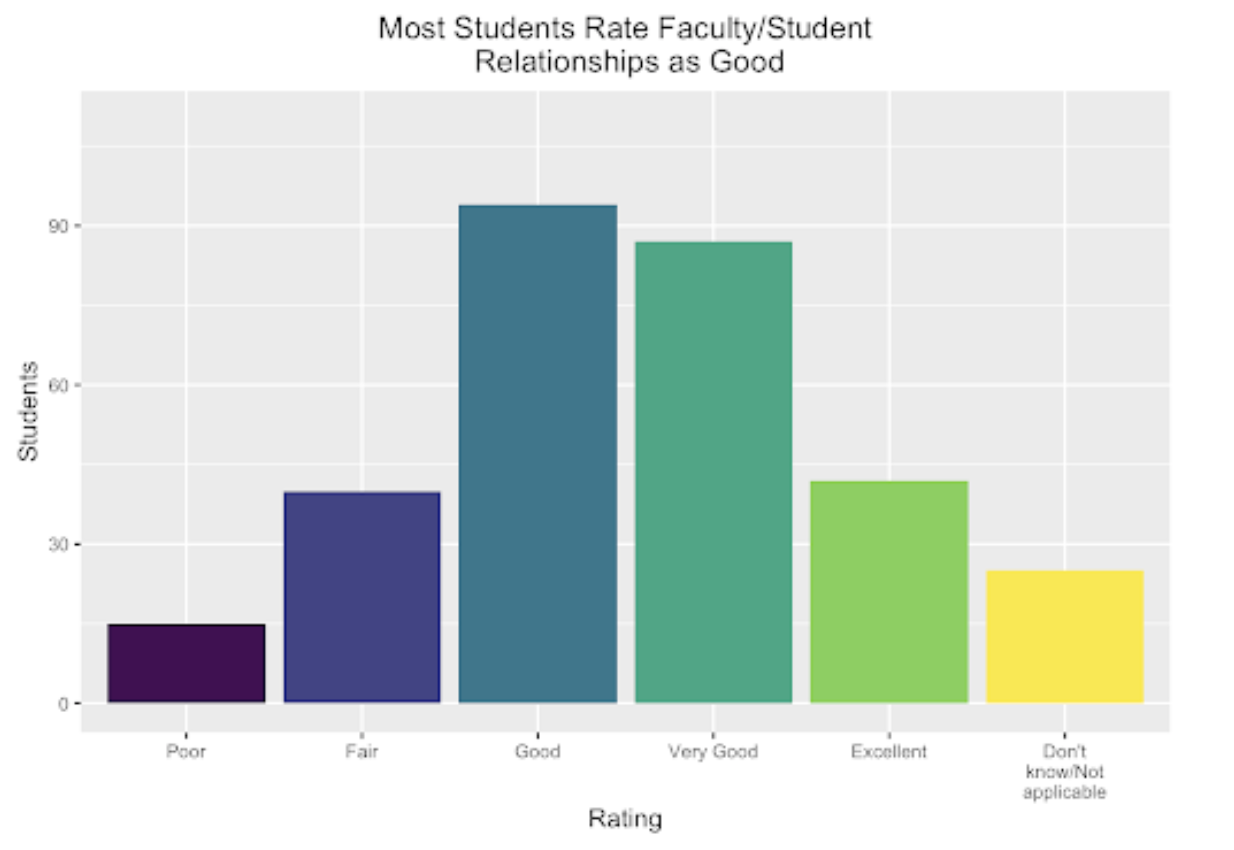

Graduate school is not “easy”, but it is more of a marathon than a sprint. Schools don’t usually release Engineering-specific sentiment data, but the University of Michigan CSE did publish the results of a required check-in survey with 223 PhD and 101 Master’s students (source). We reference this data not because it generalizes to every school, but because it may be more indicative than comments on social media (which can paint an overly-negative picture). On a five-point scale (poor-fair-good-very good-excellent), students reported faculty/student relationships as “good”:

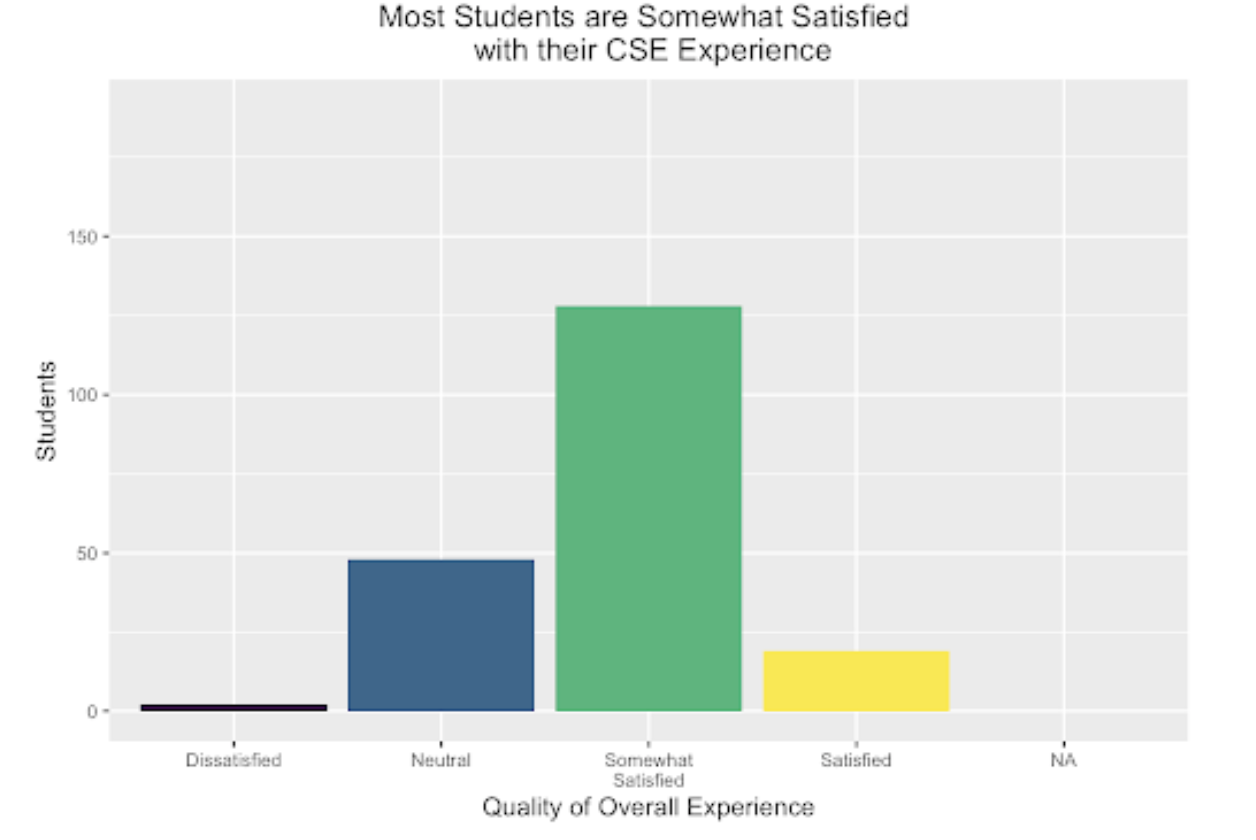

And on a four-point scale (dissatisfied-neutral-somewhat satisfied-satisfied) students reported being “somewhat satisfied” with their overall experience:

The overall sentiment reported there is guardedly positive. However, in Wes Weimer’s direct experience, your particular level of day-to-day happiness is going to depend much more on factors such as:

1 The alignment between your preferred academic style and the program’s culture (e.g., does it have a culture of “overwork” or “grinding”? do you thrive in that?)

2 The alignment and communication between you and your advisor, if you are a PhD student

3 External factors, such as mental health concerns and culture shock, and the degree to which you proactively address them and to which your graduate program supports them

One way to mitigate risks here is to apply widely, gather information during visit days and interviews that will be relevant to predicting your future day-to-day life in that graduate program, and to consider more than pure rankings when making your decisions. See elsewhere in this guide for suggestions on all of those aspects.